I first heard the phrase, “drive till you qualify” in the 1990s referring to first-time homebuyers who were priced out of Los Angeles and were heading east to California’s Inland Empire; in fact, it was probably still called Riverside County in those days. The economics underlying this eastward movement was the tradeoff between how much time you were willing to spend commuting versus and how much house you wanted. Economists would predict that those who earn the most are willing to travel the least, and so the high-earners bid up the price of housing close to jobs. That’s a theory from the early 20th century when jobs were clustered in downtowns. Things in real life started changing when high-paying jobs moved to the suburbs.

Things are changing again as jobs move to our dining room tables. Downtown office space is one of the first dominos to fall as hybrid- and remote-work are becoming the norm. As demand for office space declines, not only are there fewer workers in cubicles and corner offices, but there are fewer customers at coffee shops, lunch spots, and bars. Moreover, for downtown retailers, this decline in foot traffic and the rise in e-commerce is a double-whammy. As a result, developers and large-city governments are considering office-to-residential conversions.

Boston’s Pilot Program & Precedents

According to a recent paper from the NBER the Boston metro market is one of only six across the country where office-to-residential conversions are likely to be profitable. In an attempt to jump-start such a conversion in Boston, Mayor Michelle Wu announced an office-to-residential Downtown Residential Conversion Pilot Program, that will accept applications through June 2024.

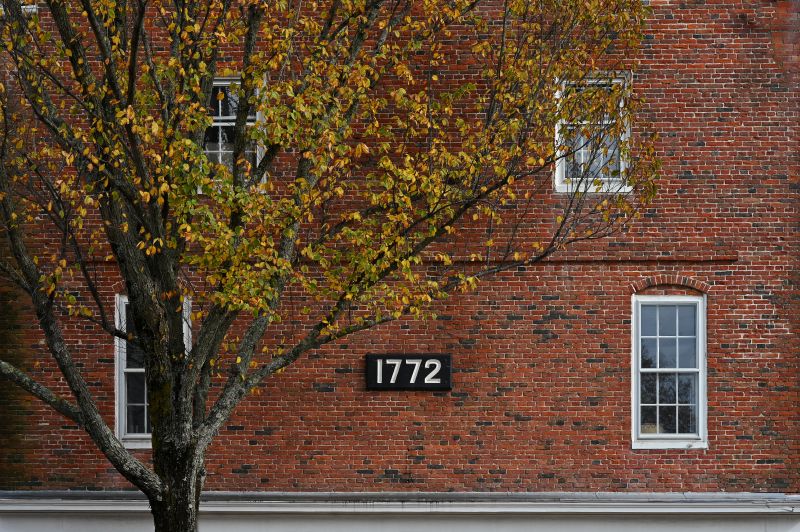

While such an effort may seem new to Boston, there are many precedents with lessons for cities and towns across Massachusetts. For example, in the mid-1990s, New York City’s 421-g program was responsible for converting nearly 13 million square feet of lower Manhattan office space into residential space by offering tax abatements. More recently, Calgary has embarked on an aggressive 10-year program to convert 6 million square feet of office space into residential, educational, cultural, and other uses. And, even small markets, such as Cincinnati, OH, Kansas City, MO, and Hyattsville, MD have all been sites of successful conversions. Office-to-residential conversion is a specific case of adaptive reuse, a process we’ve seen across Massachusetts including in Lowell, Waltham, Maynard, New Bedford, and Leominster where 19th Century mill buildings have been converted to residential and commercial uses.

Learn to surf

To understand what the successes have in common, I suggest thinking about a surfing metaphor. Changes in technology (for example, cars, highways, and public transit meant that people didn’t have to live walking-distance to work) lead to changes in tastes and preferences and this means that new products replace old. Think of this churning in the market as a wave. You can stand on the shore and let the wave crash on top of you, or you can learn to surf. Developers, owners, brokers, state and local officials who learn to ride the wave have better odds of surviving than those who wait for the wave to crash on top of them. This office-to-residential conversion isn’t just about the owners of office buildings with excess capacity, though. It’s also about jobs for office cleaners and print stores and caterers and courier services and florists. And beyond that, it’s also about less foot-traffic and fewer eyes-on-the-street and what steps in to this vacuum. This isn’t just a small swell; in some markets the wave might feel like a tsunami.

Consider this a call to action for us in the real estate industry—from sales people to developers, as well as to federal, state, and local officials, and to those who depend on local services funded by property taxes. We’ve all got a stake in seeing former offices converted into productive uses and averting the doom loop of falling property values.

Call to action.

Brokers & salespeople.

Those of us in the real estate industry have our finger on the pulse of both sides of the market. One thing that fewer deals is telling us is that those trying to sell and those trying to buy have not yet had a meeting of the minds. We need to educate our clients about the current market and seek creative solutions to bridge the gap between buyers and sellers, where realistically possible.

Investors.

When conversions are compared to ground-up development, construction time is reduced by at least two years, drastically slashing the time-to-market. The contribution of these projects to portfolio risk should make them more attractive. In addition, most of the municipal incentive programs to convert office-to-residential are also incentivizing reduced carbon emissions. This will lower operating costs and needs to be included in project evaluation.

Cities and Towns.

While Boston may be experiencing a decline in office workers that threatens the vitality of downtown, smaller cities and suburban towns are also concerned with the spillover effects of a changing industrial sector. At one time regional shopping centers and strip malls posed a threat to the downtowns whose older and smaller buildings couldn’t compete with large footprints, ample free parking, and evening shopping hours. Now those older shopping centers and suburban strip malls can’t compete with online retailers. Smaller municipalities have all-too-often been slow to understand market changes. Municipalities will need to ensure that their zoning regime is nimble enough to consider alternative uses for aging strip malls and class-B and class-C office space.

State and Federal government.

Municipalities however, will need enormous support from the Commonwealth. Current conversion experience tells us that only a small percentage of buildings are ripe for residential conversion and these tend to be pre-World War II buildings. In the Commonwealth’s smaller municipalities, these were mills, the majority of which have already been converted. What of the strip malls and class B & C offices that face weakening demand? Conversion may not be possible and they may more accurately be called greyfields– non-contaminated sites with obsolete structures; in some places these greyfields may not simply have lost value, they may have negative value. State tax credits that allow donations to nonprofits or local government at a percentage of pre-pandemic values may be one vehicle to avert the downward doom loop of falling real estate values that can affect properties beyond the vacant or abandoned site. When developers are turning brown office buildings to green residences, Federal programs created as part of the IRA can subsidize both adaptive reuse and ground-up projects.

Published August 29, 2023